A Novel Approach to Mitigate the Opioid Overdose Epidemic: The OCRM Model January 04, 2022

Tens

of thousands of people in the United States lose their lives each year to drug

overdose, and the numbers continue to mount. Since 1999, approximately 841,000 such

deaths occurred in the United States, while

the number of drug overdose deaths increased 120% between

2010 and 2018 and totaled nearly 70,630 per year by 2019.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, drug overdose deaths increased more than 20%

in 25 states and the District of Columbia. Worldwide

in 2019, around 36 million people suffered from drug use disorders.

Today,

overdose death is a leading cause of injury-related death in the United States.

To mitigate the opioid overdose epidemic, an evidence-based approach is needed and this approach should

· target and reduce opportunities for access to illicit drugs;

· use a collaborative multidisciplinary approach to improve

responses to overdose incidents; and

· have access to data for the development of mitigation strategies

and the evaluation of outcomes.

Reducing

the Accessibility of Opioids

Nearly

85% of drug overdose deaths involve illicit drugs such as fentanyl, heroin,

cocaine, and methamphetamine, according to a recent

study. Law enforcement efforts based on data from various resources are key

to reducing the accessibility of illicit drugs.

Research

has shown that a small number of prolific offenders control illicit drug

markets and that drug-sale locations form hot spots,

with a small number of addresses. Rigorous data analysis can help identify and

dismantle the network of prolific offenders in the drug-sale hot spots, which in

turn reduces the accessibility of opioids to experienced and novice drug users.

Collaborative

and Multidisciplinary Approach

Identifying

risk factors for drug overdose can lead to prevent overdose deaths. According

to a recent survey,

in more than 3 out of 5 overdose deaths, at least one potential opportunity to prevent

the death through life-saving strategies was found.

These

strategies include:

(1)

providing access

to health-care services, risk-reduction services, and the drug naloxone (to rapidly

reverse an opioid overdose);

(2)

focusing on prevention

of initial drug use; and

(3)

using multiple

drugs to treat substance-use addiction.

Indeed,

a collaborative and multidisciplinary approach is essential for the successful

implementation of these outreach strategies. For instance, a recent study examined collaborative

programs that involved local public health and public safety agencies in

Massachusetts. These programs aimed to help overdose survivors by connecting

them with harm-reduction and addiction-treatment services.

Through

online surveys and interviews with police and fire departments in 351

Massachusetts communities, the researchers were able to identify four types of effective

programs:

· multidisciplinary team visits (i.e., post-overdose visit to the

survivor to provide information and referrals for the survivor, the survivor’s family,

and the survivor’s associates),

· police visit (i.e., post-overdose visit to the survivor and to

provide a referral to public health services),

· clinician outreach (i.e., post-overdose telephone-based contact

with the survivor), and

· location-based outreach (i.e., media and word-of-mouth contact

with the entire community, including drug-overdose survivors).

These

outreach programs had in common the use of enhanced collaboration and

information sharing among stakeholders to identify drug users and the use of

timely and effective intervention efforts to prevent overdose deaths.

Access

to Data

Access

to reliable data is the key to success in an evidence-based policy. A recent study examined the

core elements of successful overdose prevention activities in four states

(Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, and Utah) that managed to decrease

their high rate of opioid-involved overdose deaths from 2016 to 2017 through

the analysis of program narratives. The study found that access to drug-abuse

data, the capacity to analyze the data, and the ability to disseminate the

findings of the data analyses played vital roles in the four states’ successful

overdose-prevention strategies. The findings were systematically disseminated through

either web-based dashboards or quarterly reports. Drug-abuse prevention

organizations in partnership with members of the local community then used the

findings to create effective program models for the prevention of overdose

deaths.

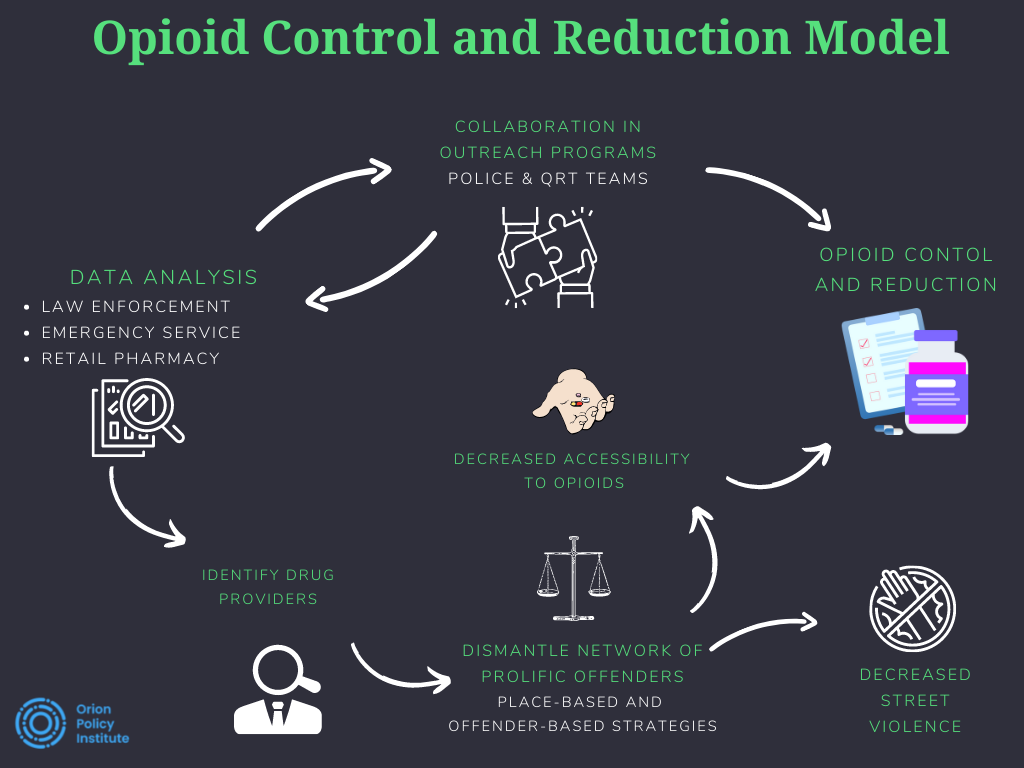

The

Opioid Control and Reduction Model

To address the need for a novel and comprehensive approach to curbing the opioid overdose epidemic, we offer the Opioid Control and Reduction Model (OCRM), which is illustrated below. The OCRM suggests that comprehensive analysis of data from three sources (i.e., law enforcement, hospital emergency department, and pharmacies) can lead to successful collaborative outreach programs aimed at controlling the rise in and ultimately reducing overdose deaths and increasing the ability of law enforcement officials to identify prolific drug offenders.

The

OCRM involves three steps:

(1) data analysis,

(2) identification and dismantling of illicit drug networks, and

(3)

development of

outreach-program quick-response teams.

Step

1: Data Analysis

The

first step in the model is data analysis from at least three sources: law

enforcement, hospital emergency departments, and pharmacies.

Law

Enforcement Data

The

proposed model analyzes law enforcement data to identify a small number of

prolific offenders who control the drug markets. Studies have found that

most gang members and prolific offenders sell illegal drugs as their primary

source of income. These same individuals also are the primary instigators of

street violence. A recent

study showed that overdose victims are connected to gang members and to prolific

offenders who sell drugs in a mutually beneficial, and sometimes

confrontational, cyclical relationship.

Spatial

analyses showed a close relationship between drug points of sale and other

criminal activities such as street robbery and prostitution. Place-based and

offender-based policing techniques, can be used to limit access to opioids,

reduce street violence, and dismantle the illicit drug network, thereby reducing

the number of overdose deaths.

Hospital

Emergency Department Data

The

OCRM also uses data from hospital emergency departments to increase the

accuracy of information about police contacts with opioid users and identify

individuals who need treatment and the support of an OCRM quick response teams.

For example, when both sets of data identify an individual with a history of

drug abuse, the police are notified and an OCRM quick response team contacts

the individual to provide proactive intervention to reduce the chances of an opioid

overdose and decrease the demand and market for the illicit drug.

Retail

Pharmacy Data

The

elimination of illicit drug networks alone may not be adequate to control the

spread of opioids. Retail pharmacy data can be used to identify individuals who

abuse their access to opioids intended for legitimate medical purposes. The

analysis of the pharmacy data provides an opportunity to control the

introduction and circulation of a medically legitimate drug for illicit

purposes in the community.

Step

2: Identification and Dismantling of Illicit Drug Networks

A

comprehensive analysis of data from the three sources (i.e., police, hospital

emergency departments, and pharmacies) will help the police to identify prolific

offenders and dismantle illicit drug-sale networks, leading to two positive

outcomes.

First,

the accessibility of illicit drugs will be reduced for experienced and novice

users.

Second,

the overall crime rate and the extent of crime victimization will drop because

the violent and property crimes typically associated with illicit drug markets

will be reduced.

Step

3: Development of Outreach-Program Quick-Response Teams

The

final step in the model calls for police to contact opioid users, gauge the

users’ likelihood of overdosing, and provide the users with information about

treatment options available in the community. A recent

study in Cincinnati found that such contacts enable police to predict at

least 10% of overdose victims before they overdose.

Current

law enforcement practices for dealing with drug users typically involve arrests

or citations. Under the OCRM, information obtained from police contacts with

drug users can lead to the development of proactive and collaborative measures

to prevent overdose deaths.

To

achieve these outcomes, police must analyze the data obtained from their

contacts with drug users and share the findings about potential drug-overdose

victims with quick response teams (QRTs) that consist of police, firefighters,

and addiction specialists.

QRTs

are “pre-arrest diversion (deflection) programs that involve interdisciplinary

overdose follow-up and engagement with survivors to link individuals to

treatment during the critical period following overdose.” QRTs

originated in Colerain Township, Ohio, and spread to communities across the

country that have suffered significantly from opioid overdoses and overdose

deaths.

QRTs

play a vital role in the OCRM because the teams focus on providing opioid users

with treatment options rather than seeking to arrest and label them as

criminals. The information obtained from these interactions can help state

governments to better understand the scope of the overdose problem in their jurisdiction

and develop programs that can prevent overdoses and thus prevent overdose

deaths.

The

QRTs also collect opioids users’ data on various aspects of drug abuse, such as

how the individual started using opioids, whether the individual’s friends use

opioids, how the individual acquires opioids, and what kind of opioids the

individual uses. The information is then added to the database pool for daily

analysis and a better understanding of the extent of the opioid problem in real-time.

Policy

Recommendations

We

provide the following recommendations for a successful implementation of the

OCRM:

· All stakeholders (i.e., policymakers, police, fire departments,

health-care systems, addiction professionals, and pharmacies) must be committed

to contributing to this model through ongoing communication, information

sharing, and the provision of necessary resources.

· For enhanced collaboration, the stakeholders must meet regularly to

discuss the needs of stakeholders that adopt the OCRM and the challenges that first

responders face when implementing the model.

· An oversight committee must be established with the involvement of

policymakers and management representatives given responsibility for providing solutions

to challenges that arise for one or more stakeholders.

· The roles and responsibilities for data sharing, data analyses,

and the QRTs should be clearly identified and communicated to all partners

through a program manual.

· Data-sharing agreements should be signed by all OCRM partners to

ensure that the necessary data are included in the databases and that comprehensive

data analyses are conducted to guide QRT outreach efforts and law enforcement

tasks related to opioid users and opioid overdoses.

· Data-sharing

agreements and protocols should clearly describe data-use guidelines,

including:

o

prohibitions

against use of the data in its raw form or the results of the analyzed data in any

way that could lead to adverse consequences for persons named in the database,

such as eviction, stigmatization, and social control;

o

protection of

privacy rights and consequences for violations of those rights;

o

the use of unclear

descriptions of data sharing processes that might deter individuals at highest

risk for overdose from calling for emergency assistance.

A

formal program evaluation must be conducted on a regular basis (e.g.,

annually). Such evaluations should include an evaluation of outcomes through quantitative

and qualitative research methods. Modifications to how the model is implemented

should be made as deemed appropriate at the end of the program-evaluation

process.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the OCRM as implemented must be conducted to ensure that the model is effective in mitigating the opioid overdose epidemic.

______________________________________________________

Orion Policy Institute (OPI) is an independent, non-profit, tax-exempt think tank focusing on a broad range of issues at the local, national, and global levels. OPI does not take institutional policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions represented herein should be understood to be solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of OPI.

_________________

Dr. Murat Ozer is an Assistant Professor at the School of IT, University of Cincinnati. He is a crime analyst and cybersecurity lecturer. He also works with Cincinnati Police Department and develops certain web-based predictive analytical systems. His research interests are primarily in managing big data sources of law enforcement agencies to generate predictive data analytics for various public health problems such as gun violence, and opioid overdoses. He is also co-founder of Peel9, a record management system and data analytics company.

Professor John Wright is a Professor at the Criminal Justice Program, University of Cincinnati. He subsequently served five years on the faculty at East Tennessee State University. Dr. Wright’s work has sought to integrate findings from a number of disciplines, including human behavioral genetics, psychology, and biology. He has published over 200 articles and book chapters and was recently judged to be one of the most prolific and most-cited criminologists in the United States. Dr. Wright consults with states and local jurisdictions and is a much sought-after lecturer.

Dr. Davut Akca completed his Ph.D. degree in the Forensic Psychology program of Ontario Tech University. He worked as a Post-Doctoral Research Officer at the Centre for Forensic Behavioural Science and Justice Studies at the University of Saskatchewan and Dr. Davut Akca is currently an Assistant Professor at the Criminology program of Lakehead University, Orillia campus.