Women In The Arab Spring Uprisings: Tunisia June 07, 2022

In this research series, we analyze the role women played in the Arab Spring uprisings and how their participation in the protest movements of the last decade impacted their gender role status. We use case studies from Tunisia, Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, and Sudan to analyze women’s activism and the current debate on women’s rights and status in the region. All case studies were derived from secondary sources. Tunisia is the first case study in our research series. Here, we analyze Tunisian women's civil and political activism since 2011, though the primary focus is on their activism since 2018. We argue that women have been the agents of change during and after Tunisia’s political transition in 2011 through various efforts including protests, putting forward candidates in the local and legislative elections, online activism, and grassroots.

As the birthplace of the largest protest movement in the history of the region and the only country that experienced a democratic transition after the Arab Spring, Tunisia has long been considered a democratic model. Although the 2011 revolution took the world by surprise with the remarkable presence of women, civil disobedience was not something new for Tunisians, particularly for women. Women networks were highly active during former President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali regime, which led Tunisia to historically rank first in the Arab world in categories pertaining to women's rights including autonomy, security, and freedom.

Women's activism during the 28-day Jasmine Revolution in late 2010 and early 2011 inspired thousands of citizens to unite against the regime's wrongdoings. Women brought social issues to the fore and demanded equal rights and freedom. Even though they often faced violent harassment from security forces, women managed to challenge the patriarchy and shake gender norms in Tunisia. Despite the achievements and a democratic political transition, the economy still challenged Tunisians while the security situation deteriorated, and political upheaval ramped up in late 2016. Gridlock and economic stagnation started testing the Arab world's sole functioning democracy, leading to the second wave of protests toward the end of 2018. Women were once again on the frontlines of the demonstrations. The election of President Kais Saied in 2019 with major support from the people raised hopes among many Tunisians because he claimed to be the voice of the people and pledged to fight against corruption. His authoritarian actions over the last year, however, plunged the country into a crisis. Public support for Saied had deterred the opposition and civil society from coming out more strongly against his power grab. Although Tunisian democracy might be slowly dying in darkness, women's continued efforts to date have proved their resilience and vision for a more democratic Tunisia.

Jasmine Revolution And Its Aftermath

The Jasmine Revolution in 2010, attributed to Mohammed Bouazizi, a Tunisian street vendor who set himself on fire in the town of Sidi Bouzid on December 17, 2010, began over government corruption and intervention into local citizen’s life. Political unrest was growing due to unemployment, lack of security, gender inequality, human rights violations, censorship, and corruption. These socio-economic conditions and a lack of government action were leading factors in triggering the protests. Tunisians rallied together to end the government’s control and censorship of the media and demanded the advancement of democratic values and respect for human rights. Unemployment levels peaked as the total unemployment reached 18.9% in 2011 during the revolution. Since 2008, Tunisia had massive unemployment rates with 30% of young graduates reportedly unemployed. The government under Ben Ali controlled the media and restricted social media use. The protests led Ben Ali to step down and flee to Saudi Arabia. The Jasmine Revolution was unique, compared with similar uprisings in many Arab nations, because women comprised a large share of the demonstrators and representatives of political parties.

In 2014, Tunisia created a new constitution that improved women's rights. With the newly implemented changes, youth and women were more actively involved in municipal and local elections, at a rate of 69% total turnout. Tunisia had its first free and fair presidential elections under the new constitution after the ousting of its former president. Beji Caid Essebsi, the founding leader of the political party Nidaa Tounes (The Call of Tunisia), won the presidency. Nationwide protests erupted again as living standards worsened for Tunisians under Essebsi. High unemployment and inflation rates, unpopular fiscal austerity measures, and concerns about corruption were general issues that Tunisians faced. The unemployment rate improved slightly but stayed at an average of 15%, with no improvement in the availability of higher-skilled jobs. Women with a higher education degree were less likely to be employed because the government was focused on creating low-skilled and low-paying jobs.

Despite this rather grim social and economic milieu, women continued to make strides in the political arena, building on the progress they made during the Jasmine Revolution four years ago. Tunisian women appeared on ballots in 2014 as candidates for political parties and as heads of election lists (i.e., groupings of candidates as used in proportional or mixed electoral systems but also in some plurality electoral systems). Before the Jasmine Revolution, women represented 7% of the heads of election lists for political parties; in 2014, representation increased to 11.26%. However, even though 47% of the parliamentary candidates were women, many women believed that they were being used as political tools to attract more women voters but not addressing their issues after the votes were cast. Reforms of women’s rights were mostly concessions intended to silence the opposition and placate foreign donors. Political parties, particularly the Islamist democratic party Ennahda which presented itself as moderate and willing to make considerable concessions –mainly regarding women's rights– enjoyed wide support from women. Therefore, women’s rights groups became a public relations tool aimed at portraying the Tunisian state as amenable to women’s interests. This top-down approach to women’s rights reflected “state-imposed” feminism that limited independent women's activism. While women also enjoyed the concessions and were able to push for meaningful reforms, their voices were disproportionately underrepresented in the government policy formulations.

The Years 2015-2017: Protests Bring Progress

During this period, a massive number of women participated in demonstrations, protests, and other political efforts for greater rights – primarily freedom of expression and equality. Women spoke up and persisted in the fight, ultimately accomplishing their objectives. One of those objectives was for women to be more politically active. For instance, in 2016, more women were elected members of the Tunisian Parliament than in the French Parliament. This milestone represented a crucial victory for women’s participation in Tunisian politics; however, only three women were members of the government that year. It was a step in the right direction on the road to equality, but women still were not fully viewed as equal participants capable of working in local and national government positions. Women were not deterred and continued the fight, focusing now on ending violence against women.

Demonstrations to raise awareness about the issue and a call for action were successful. In March 2016, Espace Tamkin opened a women’s shelter, which provided safe space for 30 women and children for three months at a time. Tamkin also started a work training program for the shelter’s residents. Through their vocal demonstrations, women were able to engage the country in conversations about gender-based violence and pave the way for the opening of the shelter.

The following year, 2017, multiple significant achievements for women’s rights were achieved. On National Women’s Day, for example, then-President Beji Caid Essebsi created the Commission for Individual Rights and Freedoms in response to women’s continuous demands for more freedom and equality. The commission was responsible for recommending changes to the Tunisian Constitution that would further the equality for women. Since its creation, the commission has been chaired by a female member of the Tunisian Parliament, Bochra Bel Haj Hmida. Another example of how women’s political activity paid off is the passage of several laws, one of which required the prosecution of rapists. Before 2017, a male rapist was able to avoid punishment if he married his victim. Women’s calls for equality ended that law. In addition, the portion of a 1973 law that prohibited Muslim Tunisian women from marrying non-Muslim men while allowing Muslim Tunisian men to marry non-Muslim women was overturned. The revised law also raised the age of consent for women from 13 to 16. These changes were enacted because of women’s political and civil activism.

Tunisian women, through continuous activism and demonstrations following the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011, made significant strides in their quest for greater freedom, more rights, and equality with men. These achievements proved that Tunisian women are capable of pushing for change and getting Tunisian men and the government to pay attention to their demands.

2018: Tunisians On The Streets Again

Tunisians continued to protest the actions of the government. By 2018, the rallies had become contentious, much like they were in 2011 when activists called for the government to scrap new austerity measures, including a hike in fuel prices and taxes on goods. These demands developed into a wave of protests that turned violent, resulting in the arrest of hundreds of protestors. The initial protests in late 2018, however, ended when a journalist set himself on fire over economic conditions in the country. This event angered more Tunisians and pushed them into the streets, which then led to a backlash from the security forces.

The year 2018 also was marked by what appeared to be the start of a revolution on women’s rights. The Essebsi administration, for instance, began to upend Islamic laws and taboos on marriage and inheritance by instructing the Commission of Individual Liberties and Equality to draft a proposal for changing the country’s inheritance law to give women equal marriage and inheritance rights. The revised law was revolutionary for Tunisian and Muslim women everywhere. Critics of President Essebsi were displeased with the president’s directive, arguing that he had endorsed “state-imposed feminism” and used women’s rights as a political agenda to distract the nation from other issues and to secure women’s votes for the upcoming elections. These critics, however, failed to acknowledge that the political concessions had enabled Tunisian women to enjoy a higher social status and greater political, civil, and personal rights.

The approval of the equal inheritance bill by the Tunisian cabinet, despite the critics’ objections, showed that a public revolution against a national dictator could turn into a private revolution against the tyrants that women faced in their homes and on the streets. Women’s rights activists continued to campaign for changes in Tunisia’s laws, even though support for their cause was not universal. Some Tunisians agreed with the legal changes and showed their support through protests, while thousands of others took to the streets to object to the new gender-equality laws, stating that the laws were contrary to Islam. These protests against more progressive laws in favor of women’s rights, while contrary to the ideals of the Arab Spring movement, reflect the fragmentation of Tunisian society.

Overall, the protests in 2018 were an example of “on-the-ground” activism supplemented with some political and legal activism. The work paid off, enabling women to be included in 47% of local governments in 2018. While social media likely played a role in the organization and spread of the 2018 protests, online activism was not notably high.

2019: A Pivotal Year for Tunisia

The political decentralization and transition of presidential and legislative power that emerged from the 2018 local elections hinted at a similar trend in 2019. The 2019 election results indicated an overall rejection of the parties and politicians who had led the government since 2014. Newcomers, independents, and non-career politicians were favored. Kais Saied, who at the time was a professor of constitutional law, received the largest share of the vote with 18% in the September presidential election and 73% in the run-off election a month later. For many, Saied represented justice and the rule of law. His vow to protect women’s rights helped him to secure the support of women. His independent standing also attracted the endorsement of several former candidates from the other parties, including Ennahda. Saied received the support of nearly 90% of the young voters (aged 18-35), which indicated a heightened sense of activism among the country’s youth.

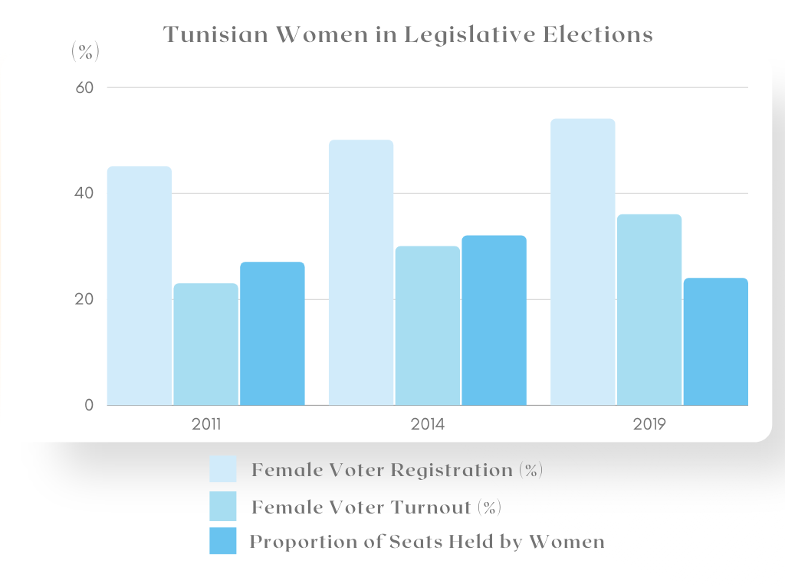

Overall voter turnout, however, was low. Only 3.5 million people – 39% of registered voters– cast a ballot. Among the candidates, women were underrepresented in both elections. Electoral lists are obliged to alternate between men and women candidates, though no party nominated a female candidate. Out of the 97 candidates who applied for presidential candidacy, only 11 of them were women. The High Independent Authority for the Elections approved 26 female candidates, but the final list included only two women. During the legislative elections, 36% of registered Tunisian women cast a ballot –10% fewer than registered Tunisian men who cast a ballot. Women won only 22% of the seats being contested –10% fewer seats than in 2014 (see Figure 1). The 2019 parliamentary elections highlight the need to implement further changes to increase women's representation in Parliament. Despite the high registration and turnout rates for women, the number of women elected to office has dropped to the level seen after the 2011 election –an alarming setback for Tunisian women.

Figure 1. Changes in Female Voter Registration, Female Voter Turnout, and Proportion of Seats Held by Women in the Tunisian Parliament for Election Cycles 2011, 2014, and 2019. Source: Tunisia High Independent Authority for Elections (Instance supérieure indépendante pour les élections).

Although sporadic and much smaller in-person protests continued over the marginalization of women, deteriorating socio-economic conditions, and rising fuel prices, online activism ramped up. Tunisian women launched social media campaigns on sexual harassment under the hashtag #EnaZeda (#MeToo). The hashtag was in response to a video of a politician from the Qalb Tounes Party, the second-largest party in the Parliament, masturbating in front of a high school. The video and photos were initially posted in a private Facebook group by a 19-year-old high school girl, who accused the parliamentarian of sexually harassing her outside her school.

Her posts soon prompted an online movement, where women of every age and background began to share their sexual harassment experiences. Thousands of women raised their voices against gender-based violence in Tunisia, with more than 70,000 posts and comments. Many of these women accused Tunisian politician Zouheir Makhlouf of sexually harassing them; however, Makhlouf denied the allegations and was not charged with a crime. Even though Tunisia has laws to combat harassment and violence against women in the workplace, lawmakers have immunity from prosecution, which in turn discourages women from filing formal complaints.

Many commentators and activists who were involved in the #EnaZeda campaign were detained and interrogated by the Tunisian National Guard. Saloua Charfi, a female professor at the Institute of Press and Information Sciences (IPSIE), was among them. Like Charfi, Maha Naghmouchi, an aesthetician-in-training, participated in the #EnaZeda movement and used vulgar terms about the police in her online posts. Although she deleted one such post a few hours after it went live, she was arrested and interrogated by the police. Despite these government intimidation campaigns, thousands of women like Charfi and Naghmouchi continued their activism on the ground and online.

2020: Tunisia And The COVID-19 Crisis

Only one major positive related to the concerns of women occurred in 2020. In response to an increase in the reporting of domestic violence cases by women during the COVID-19 pandemic and demands from Tunisian women to provide more spaces for women, the Ministry of Women, Family, Childhood, and Seniors opened a new shelter in April for women who had been the victims of domestic violence. Cases of domestic violence, which increased dramatically around the world during the pandemic, reached high levels in Tunisia as well. During the government-ordered lockdown from March 20 to June 8, calls from women to report domestic abuse increased by five times compared with 2019. Between March and May, the government received more than 7,000 reports of domestic violence, including 1,425 reports in just the first month of the lockdown (see Figure 2). Despite a large number of domestic violence victims, only 350 women per week had access to shelters provided by organizations such as the Tunisian Association of Democratic Women (ATFD).

Figure 2. The number of Domestic Violence Complaints the Ministry of Women, Family, Childhood, and Seniors Received During the Three-Month Government-Mandated COVID-19 Lockdown, April-May 2020. Source: Tunisia Ministry of Women, Family, and Seniors (Ministère de la Femme, de la famille et des séniors).

Women also faced difficulties in obtaining protection orders from their abusers when courts were closed during the lockdown. As a result, many women began to vocally criticize the government for not taking their complaints seriously. Women’s activist organizations, including the ATFD and the Tunisian League for the Defense of Human Rights (LTDH), came together to issue a statement regarding increased complaints. The government, however, did little to protect women from their abusers. The opening of a government-sponsored domestic abuse shelter in 2020, thus, was the only major achievement for women that year.

Setbacks for Tunisian women, on the other hand, were far more numerous during the pandemic lockdown. As discussed earlier, in 2018, the Commission for Individual Rights and Freedoms recommended that the 1956 Personal Status Code, which states that males are to receive double the share that women receive in inheritance from parents, be amended to say that men and women should receive an equal inheritance. The Tunisian government, however, did not consider this recommendation until 2020. The government’s decision was not favorable to women. On International Women’s Day in 2020, Saied announced that he did not support equal inheritance. This statement was a major setback in the fight for women’s rights and made clear that Saied does not support equal rights for women, despite the implementation of multiple gender-equality initiatives during previous administrations.

In the last month of the year, Mohamed Afess, a Tunisian parliamentarian from the conservative al-Karama coalition, stated that women’s achievements have ruined women’s honor. Afess’ statement caused a major uproar from women’s activist groups, all of which criticized his statement for being insulting to women who were simply advocating for their basic rights. Following his statement, several civil society organizations filed lawsuits against Afess. While many Tunisian women are continuously advocating for their rights, Afess’ statement shows that some segments of the Tunisian society do not support women’s rights and equality.

The year 2020 ended with little to boast about in terms of the advancement of women’s rights. The lone victory was the opening of the state-sponsored domestic abuse shelter. Unfortunately, domestic violence cases rose greatly during the COVID-19 pandemic, prompting many women to criticize the government for not doing more to address the issue. Statements by Saied and parliamentarian Afess further reflect the reality that despite the continued activism of women, men in government positions often do not support women's equality.

2021: More Protests

Near-daily protests across the country marked the start of 2021. In January, protestors on Habib Bourguiba Boulevard called for “the fall of the regime,” a chant reminiscent of the first wave of the Arab Spring. The sentiment proved that since the first protests, while Tunisia formed a democratic government, democracy had not been delivered to the people because Saied’s authoritarian practices surged. He fired the Prime Minister and suspended the Parliament on July 25, further pushing the country into a political crisis. Despite the wide support from the majority of the population, Saied’s move toward broadening his grip on power raised deep concerns among the opposition, who called his actions a “coup.” Saied, however, had thousands of supporters on his side, who celebrated his actions on the streets (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Supporters of President Kais Saied gather on the streets to celebrate his suspension of the Parliament and the firing of the prime minister. Opposition groups criticized the revelers for siding with authoritarianism over democracy. Photo by Zoubeir Souissi, July 25, 2021, Reuters.

Women activists protested vigorously online, on the streets, and in the political sphere. Women did not collaborate across party lines, but they steadily fought for the same cause –women’s rights. The non-governmental organization Aswat Nissa launched the Women’s Political Academy, which has trained more than 200 sitting or aspiring women politicians and community leaders below the age of 35 on how to integrate gender issues into public policies and work across party lines to advance women’s rights.

The year 2021 proved that overall, Tunisian security forces had not changed their ways since 2011 and continued to use violent measures to quell anti-government protests. The issue of women’s rights still was not on the protest agenda, nor was part of any proposed major reforms. Progressive parties stood up for women’s rights only when it suited them. This utilitarian approach to women’s issues resulted in women constantly competing for a small number of positions in the government and, when in office, finding little willingness among themselves to cooperate and work across party lines. Efforts that could have been directed toward issues and laws pertaining to women’s status typically fell victim to positional competition. The result was less than optimal cooperation among women legislators. Thus, women’s rights remained a pawn on the political chessboard in Tunisia. Tunisia was the only country during the 2011 uprisings to successfully create a democracy, even though it had and continues to have its flaws. Tunisia may not be on the verge of collapse, but the issues that arose during the 2021 protests proved that a collapse was not outside the realm of possibilities.

2022: Where Is The Country Headed?

Ten years after the Jasmine revolution, nearly nine in 10 Tunisians believe the country is heading in the wrong direction, and the majority thinks that democracy is the best form of government. Tunisia’s economy now grows at about half the rate it did before the revolution; inflation has roughly doubled over the same period, and the unemployment rate has risen. As the political crisis between Saied and the Parliament deepens, Tunisia faces the prospect of losing the gains made during the last decade. Over the last nine months, Saied has solidified his nearly absolute power in the name of the Tunisian people. He pledged to adhere to the constitution and protect people's rights; however, he continues to abuse his power – earning him the nickname “RoboCop.” In the winter of 2022, he called upon the people to join in a national dialogue to form a new constitution. About half a million Tunisians participated in this online consultation – showing that although he has the support of the majority, more people have lost interest in his reforms since his power grab last year.

In January, security forces beat demonstrators with sticks to disperse an opposition protest against the president. Saied’s actions to tighten his grip on power have long undermined public confidence in his leadership. In addition, his policies and practices appear to be trending more and more toward authoritarianism. On February 6, he dissolved the Supreme Judicial Council, raising fears about the independence of the judiciary. Meanwhile, civil society organizations are facing new restrictions. To express their concern that democracy in Tunisia could devolve into a one-man rule, women's organizations such as the National Union of Tunisian Women (UNFT) and the ATFD have arranged meetings with Saied and participated in rallies. Political circles, becoming fearful of women’s increased efforts, are engaging in activities to silence these organizations. After accusing civil society groups of serving foreign interests, Saied drafted a law in March 2022 that would ban all foreign funding for NGOs in Tunisia, regulate civil society movements in the country, and essentially give government authorities carte blanche to meddle in the way civil society organizations operate, raise funds, and what they say in public about the issues Tunisians are facing.

Despite the protests over Saied’s suspension of the Parliament last year, he nonetheless dissolved the Parliament on March 30. While political unrest continues, the dissolution of the legislative body could be the most severe political crisis for Tunisia since the Jasmine Revolution. The president has promised to draft a new constitution and put it to a referendum this year; however, he has failed to keep his promises thus far. Fearful of what lies ahead, thousands of protestors once again took to the streets, accusing the president of a “failed dictatorship," and demanding his removal. Samira Chaouchi, one of two deputy speakers of the Parliament, was among the lead activists who chanted, “We will continue to resist the coup and we will not retreat. We will not accept this dictatorship!” Her resistance inspired many more to revolt against the unlawful practices of the government. Although Saied has remained silent about the people’s demands, citizens continue to speak up against the injustices and authoritarian tendencies of the government. Meanwhile, the support of the silent majority further deepens the societal divide in the country.

Conclusion

After 10 years of determined effort, Tunisian women have historical successes to celebrate. Tunisia is considered a regional leader in advocating for women's rights, as its laws include relatively better gender equality provisions than do the laws in most other countries in the region. However, women are far from having equal representation in many spheres of life. The glass ceiling for women in political life remains unbroken, and women continue to suffer from domestic violence, despite laws that have been enacted to prosecute abusers.

Although the pandemic further increased the number of domestic violence victims, social media has been a critical tool for women to develop and share online resources. On one hand, the Arab Spring uprisings of 2011 and 2018 have provided a voice for Tunisian women and paved the way for more informed discussions about gender roles in the country. On the other hand, freedom of association, speech, and movement is facing a serious threat from the government. Saied’s totalitarian drift has swept away any glimmer of hope that the Arab Spring would bring lasting democratic reforms to Tunisia and all hope that women would finally achieve gender equity.

On the road ahead, a deepening socio-political polarization may push thousands more Tunisians onto the streets, possibly exacerbating an already increasing level of police brutality. The military may intervene, leading to a possible shift from non-violent enforcement to the use of violence and force. Saied might hold a constitutional referendum and draft a new electoral law that could eliminate the Parliament or diminish its power. A more hopeful scenario would include the efforts of civil society organizations that have been developing a roadmap that could potentially provide adequate checks on Saied’s power. This road map, however, should include steps to address the various issues Tunisia is facing and provide opportunities for negotiations between the government and the people. The escalating political crisis is alarming for women in key positions. The Tunisian president's steps to place the country's institutions under his control further restrict women's political activism. It is essential, therefore, that women's civil activism continues to push for the return of legitimate institutions and the preservation of gained rights. It is essential also that the Biden administration and the heads of European governments (i.e., Tunisia’s largest economic partners and diplomatic supporters) consider Tunisia's democratic setback in their assessment of financial aid. Conditions should be set in place to pressure Saied to put the needs of the people above his personal ambitions.

Tunisia's democratic trajectory and the future of women's rights remain to be seen. Tunisian women have long benefited from state feminism and their continued activism has enabled more initiatives for women’s recognition, representation, and inclusion, primarily in the political sphere. While the Tunisian women’s movement continues to prioritize action on domestic violence and political representation, gaps and deficits in women’s socioeconomic status across the country remain challenges to the movement moving forward. The Tunisian people, however, have proven their resilience and commitment to democracy time and again, with women on the frontlines. It is, therefore, ultimately up to the courageous Tunisian people to continue their journey to democracy.

______________________________________________________

Orion Policy Institute (OPI) is an independent, non-profit, tax-exempt think tank focusing on a broad range of issues at the local, national, and global levels. OPI does not take institutional policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions represented herein should be understood to be solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of OPI.